The Naked Spur

Alexander Adams, London: Exeter House, 2025, 304pps., pb., £14.93 (Amazon)

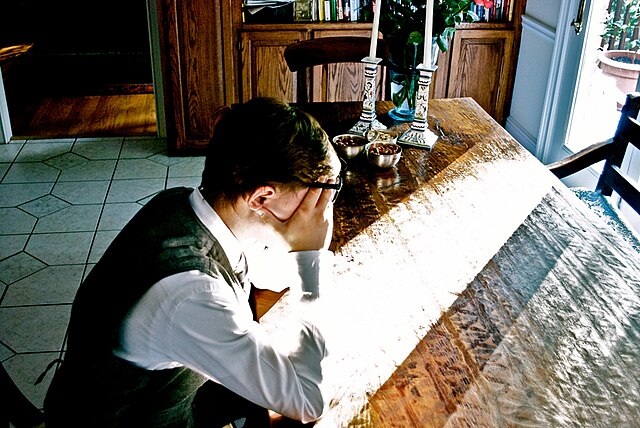

In 2007, a burned-out young British artist arrived in Berlin from London. He rented a frigid apartment in the worst district of the city, and subsisted on coffee and chocolate while he hammered out the draft of a novel ‘inspired’ by his recent bad experiences in London, perversely using an old-fashioned typewriter instead of a user-friendly laptop. In a May 2025 article published on his Substack, he explained his mindset at that time: “I wanted to do it the difficult way because that was what made it real. Suffering – even self-inflicted unnecessary suffering – made any achievement more worthwhile because it had been hard won.” Alexander Adams’ grimly determined mindset has changed little since that time, although he has subsequently found not just some artistic success, but also greater acceptance and understanding of himself, and the art world in which he operates as a rare ‘conservative’ presence.

Adams made desultory attempts to publish his manuscript at that time, but following rejections put it away for almost two decades. Having come across some of the artwork of that period again while working on a new project, he feels it is now a good time to publish, to set his present work in context and reveal more of his backstory to his subsequently acquired audience. It will also, he feels, be purgative – “a personal accounting” that can balance his books.

Novelists, as we know (or think we know) write largely about themselves, but The Naked Spur really is based very closely on actual experiences. The protagonist is a thoughtful artist called “A,” he is highly skilled but commercially unsuccessful, and he lives where Adams used to live, and bristles with his former emotions – a frustrated, lonely and resentful figure surrounded by equally atomised but usually far less intelligent individuals.

In desperate need of money, and in search of any kind of recognition, A has a cunning plan – to sell customised nude pictures to wealthy sensate individuals who wish to parade not just their wealth as patrons of the arts, but their allegedly ‘liberated’ selves. It is a cynical and even seedy concept, designed to prey on the gullibility and vanity of self-styled ‘sophisticates,’ and the reader is not sorry when it fails, despite the strenuous efforts of A and several revolving-door associates and collaborators.

One does, however, develop some sympathy for A himself – an impressive person reduced to such resorts, who has besides come to believe in the worth of the art he is producing for such shabby purposes. Yet in the end the failure of the scheme was good for him, as well as for society – because it forced him to do something infinitely more useful with his talents than flogging pornography-adjacent images to the wealthy and credulous. And he has done many more useful things in the years since – produced artworks which are held in world-famous collections, staged powerful exhibitions, edited anthologies, and written insightfully about the state of the arts in many articles and reviews, and important books like 2002’s Artivism, which I reviewed here.

In the present book, the London of some twenty years ago is excellently evoked in innumerable gritty details. I lived in Deptford around the same time as the artist, and his landmarks were also mine – the handsome baroque church of St Paul’s, the Bird’s Nest pub, the High Street, the Docklands Light Railway, and immediately across the river Canary Wharf still rising around its central silver tower. The sadness and shabbiness he shows in such photorealist detail – the drunks and their vomits, the glue-sniffers, the unhygienic takeaways, the graffiti and litter, the futile casual encounters and conversations in grubby rented rooms, the sleazy ‘top shelf’ magazines in newsagents – all that too rings authentic, the underbelly of the brittle metropolitan world A so badly wants to break into. It is closely observed, and faithfully depicted.

But sometimes the detail takes up space that might have been better devoted to character development. Some of the characters in The Naked Spur seem insubstantial, at times almost staffage, representations of sets of attitudes rather than real people. Even A hovers on the edge of focus, an observer rather than instigator, a reactor rather than a principal. He is obsessed with his single big idea, and concentrates so hard on trying to bring it to fruition that everything else is forgotten. The project becomes an end in itself, the artistic vision increasingly reduced to individual brush strokes, and the logistics of packing crates and pots of varnish. For a book about ‘nakedness’ and ‘spurs’ – a book, furthermore, which the author has described as “very personal” – A’s character and motivations seem rather opaque.

Insofar as we can see into A’s soul, it can seem sere. Sitting in that freezing flat in Berlin, he was writing in “self-aware replication” of his project’s failure. He goes on, “I would become an isolated broke author engaged in a private unprofitable gesture writing an uncommissioned novel about an isolated broke artist engaged in a private unprofitable gesture painting unsaleable pictures. The novel would be as sterile as the paintings – uncontaminated by commerce, uncompromised by any consideration of propriety.” As an explanation of what he was doing and thinking at that time, it is bracingly honest, but it sounds like a rather unappetising fictive formula.

The prose style is generally austere, a welcome change from the pretentious word-salads of the arts ‘establishment.’ This amorphous entity is the hinted-at villain of the piece, a jellyfish without a central brain but capable of responding quickly to environmental stimuli (money, or trending politics), and of course armed with poisonous nodules. Whatever the merits of A’s art (and Adams really is a superb craftsman) he was destined to be included out of lionisation or major grants by early Noughties arbiters – and he did not exactly help himself with his choice of subject matter. Adams’ more recent art must similarly sometimes have found itself treated with suspicion, because of his now publicly known political views; it is a testament to his abilities that he has achieved as much as he has against such odds. His art is luckily likely to last longer than that of many of his establishment-embraced contemporaries.

One slightly wonders who the novel is addressed to, apart from himself. Some of Adams’ generally conservative admirers and followers might even look askance at these productions of the artist’s youth – although conservatives are frequently more forgiving than the liberal-minded, and more morally complex. All would doubtless welcome a more recent autobiographical outline, in which the tough but callow young A can be balanced with the thoughtful and experienced Alexander, the ‘naked spur’ clad more warmly. For now, at least we have a striking study of a clever and interesting man at a low ebb in his life, losing all illusions to his and our advantage.