15th April 2020

“The firmament is blue forever, and the Earth

Will long stand firm, and bloom in spring.

But, man, how long will you live?”

Li Bai, The Chinese Flute: Drinking Song of the Sorrow of the Earth

Classical music fans may recognize the 8th century poet’s words as forming part of the lyric of Mahler’s lushly Romantic Song of the Earth. Unfocused sentiments of this kind, strange music of this sort, ran through my mind yesterday, as I cycled through an empty country with a cold wind in my face, but the sun on my back. The pleasures of melancholy are as old as humanity, but infinitely younger than the earth.

Nature was carrying on brilliantly as humanity shiveringly imagined overthrow. The erstwhile masters of Creation, famously promised

dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth

looked wistfully out of windows as dandelions and marsh marigolds vied to out-yellow each other. A female sparrowhawk arrowed under apple trees. Pond-skaters and whirligig beetles moved in dykes, and a male minnow circled monomanically as he milted the eggs just extruded by his mate. A buzzard flapped lazily away as I approached, but became less lazy as he was dive-bombed by a crow, which came all the way across a field specifically to attack. The crows must be nesting close, and their own soon-to-hatch brood was likely to be raised partly on songbird chicks – but now, the black patroller was ‘moral’ crusader, hypocritically outraged by proximity of a bigger predator.

The silence of cycling allowed me to come unnoticed on cock pheasants, the wonderfully exotic, unintelligent interlopers with their gleaming greens, reds and russets. They stared in alarm to see me, or flattened themselves in a touching attempt to disguise themselves against the soil-tones, while I gazed at them in love, dreaming of future pheasantries (if I ever earn some real money from writing).

The contrast between vivid nature and vapid humanity was marked as I came to the first of the three medieval churchyards along my route. The churches themselves were closed, but all around were the spoor of centuries of births, marriages and deaths – hundreds of lives recorded on headstones ranging in date from the late 18th century to 2019.

Whole families lie low around fourteenth and fifteenth century towers and later naves, perhaps easier together in death than they had ever been in life – all their unevenness ironed out, ancient disagreements stilled in perpetuity, the stones remembering only inadequate aspects, like chips of stone off great boulders – the names and dates, their relationships, that they had been beloved, were much missed. One had been a rector. Another had ‘used his beautiful voice to the glory of God’. Another had been ‘Hydrographer to the Navy’. In one churchyard, thirty or so identical stones gave the names and ranks of flyers (this is RAF country), some of them who had come from Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, but whose bodies now lay elsewhere, some ‘known only to God’. Two of these Commonwealth war graves bore even less information – ‘An airman of the Great War’. Not even the gravestones to pre-18th century generations have survived, and we have to summon up these ghosts without material aids. An ex-landowner in one of these unassuming and still remote-seeming parishes was one George Smith, father of Captain John Smith of Jamestown fame.

One of the churches itself has disappeared, on a site where there had been a chalk church in the 11th century (in the Marsh, building stone is always in short supply). The same chalk was reused to rebuild the church in 1837, but then the church fell into disuse, and the whole lot was swept away in the 1990s. The Victorian font remains, in the demarcated footprint of the building, carefully covered to avoid being soiled – a trace element of old respect. The only songs heard at St Edith’s now are the cheering carollings of passerines, or the cawings of rooks, the Anglican bird par excellence with their sable plumage and stately walk, for all the world like 18th century divines.

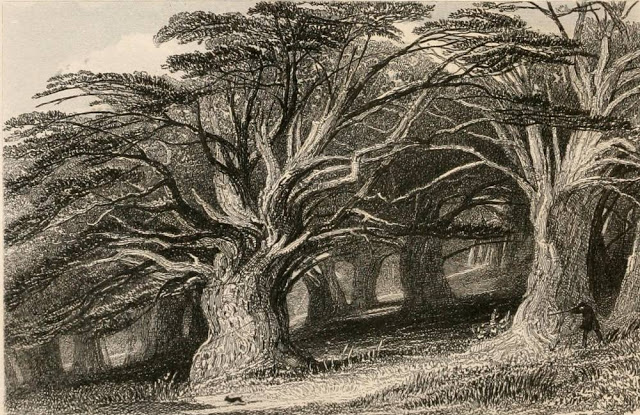

By far the most impressive remaining element in that churchyard is the storm-battered, human-battered yew that bulks above graves that never feel the sun – huge, lopsided, and missing the top half of its trunk. Judging from the thickness of some of the lateral branches it must have been 50-60 feet tall. Almost perfectly round cones the size of tennis balls strew its sun-starved feet, destined 99% of them to fail, but below them, the roots of the parent tree reach deep into England. The tree may have been a sapling when the chalk church was built. Yews elsewhere can be thousands of years old; this one is ‘just’ several hundreds. They were a symbol paradoxically of immortality and mortality before even Christianity was heard of hereabouts. We planted small yews in our garden around a statue of Pan; they’ll outlast us, and maybe even our 180 years-old house, swelling slowly with toxic berries year on patient year, until some day the sea breaks in, and the whole coast moves west.

Another of the churchyards has even more impressive yews, with a different bark. At St Edith’s the bark is rough but evenly stippled – brown-red and in places silvery. At St John the Baptist, the trunks are dark-brown and deeply grooved, almost snakelike, as though many trees have fused, and the resultant superorganism has a purposeful life of its own. One stunted tree twists impressively around a much larger one in an attempt to snatch some light, with results suggesting physical deformity – except that you can feel the tree is vigorous, and when you stroke its trunk, beneath the dry and papery texture there is a sense of some giant thrum. The equally funereal ivy that starts up some can be a strangler of lesser trees, but it has met its match in these, its thickest roots and stems no match for these leviathans of longevity.

Pedalling home eventually, gratefully under the sun again, past new-leafed hawthorns, over glinting rivers, overflown by birds who don’t even see me, or much care even if they do. Nature is cold, indifferent, inhuman, like Auden’s avifauna in The Fall of Rome, who

Unendowed with wealth or pity,

Little birds with scarlet legs,

Sitting on their speckled eggs,

Eye each flu-infected city.

But it is also beautiful – maybe all the more so for reminding us of our relative insignificance.

Evocative and timeless.

Thank you!